Experience leads to increased competency

As a worker proceeds through their career and gains experience and perspective, they generally become more competent at their position. In certain cases, particularly challenging times may accelerate this process and potentially separate out the competency in performance of those who experienced the event and those who did not. Examples could include a company merger, a large lawsuit, or needing to perform a rare surgical procedure.

For the field of veterinary public health, the 2015 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) outbreak could be classified as one of these times. The transboundary disease outbreak came in on a scale not many had experienced before. 232 premises were affected, and 50 million animals needed to be culled, with an estimated economy-wide impact of 3.3 billion dollars. Over 3,600 responders were required to contain the outbreak.

Responders and other stakeholders involved consistently mention strained resources and challenging times when reflecting on the outbreak. But there was also a large component of adaptation and learning. Procedures in place at the start of the outbreak were replaced with better methods. Communication gaps were identified, and efforts were made to mend them. Restrictions and challenge bred creativity and competence.

What happens to that experience

The agriculture emergency response system is better prepared for the next emergency due to the HPAI outbreak. Individuals within their positions have been put to the test and can draw upon that experience for the next outbreak. Yet one stakeholder, in an anonymous interview, raised a troubling question. What happens to all this gained knowledge that these individuals have? How much is trapped within them and lost as they move on with their careers and life?

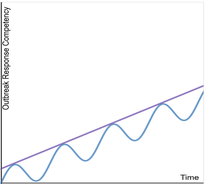

Institutional knowledge loss is a term that has been used in business settings to describe the gained knowledge from experience that is lost when a worker leaves a position or a company. In business settings, as a one person replaces another, this can lead to serious yet hard to quantify effects on operational efficiency and profit. In disease outbreak settings, the consequences could be potentially more dire. The graphic below illustrates this principle.

In theory, disease response system competency at both the individual and system level improves over time, represented by the straight line in the graphic. Turnover and change in personnel in a position or overall in an agency, however, can dampen that competency as workers take their knowledge out of the position or system, illustrated by the lower sine wave. The difference between the ideal response competency line and the lower sine wave is institutional knowledge loss. There are many more unknowns than knowns about institutional knowledge loss, especially in the disease outbreak response setting. How deep do those troughs go when a position is turned over? While in this graphic the losses in competency are temporary, does the institutional knowledge loss wave ever fully recover to the point of the ideal competency line? The graphic reflects general knowledge and competency, but how many specific competencies and experiences are lost forever with each turnover? Most importantly, how do these losses affect responses in a real outbreak setting?

Another way of visualizing the problem can be through thinking of an outbreak response as a spider web and imagining that each point, or node, in the web is an individual within an outbreak response and that all the connections running out from that point are their roles and responsibilities connecting them to other individuals. What happens to the integrity of the web when a node is removed, which could be institutional knowledge loss as an individual moves on? What if that node had many connections? How fast can they be replaced, and what happens if a gust of wind hits the web in the meantime?

Plans of action

More research will be needed to quantify institutional knowledge loss and the exact damage it can have to disease outbreak responses and other public health institutions. But several methods for minimizing the losses are already in existence.

Organized mentoring and training programs with gradual position transitions can go a long way for effective experience sharing. Recognizing the benefits of continuity of operations, many business hire replacements at an earlier time to facilitate these moves. Job sharing can help as well, by nature distributing experience through the system. Gaps in official forms where useful information may not be required should be amended, or ancillary material standardized to be attached. For example, there may be large gaps in recording what challenges were overcome to produce the final output required. And recording protocols and procedures into easy-to-follow practical manuscripts or videos can provide a permanent reference for gained knowledge.

There are more described methods for minimizing institutional knowledge loss, but a subtle mentality shift may be the most effective solution for this problem. Traditionally, individual performance has been the measure of success, with much modern business thought shifting to pure output measures (what did you produce?). Especially in public health roles, though, perhaps having others be able to easily replicate that output should be a higher priority as well.