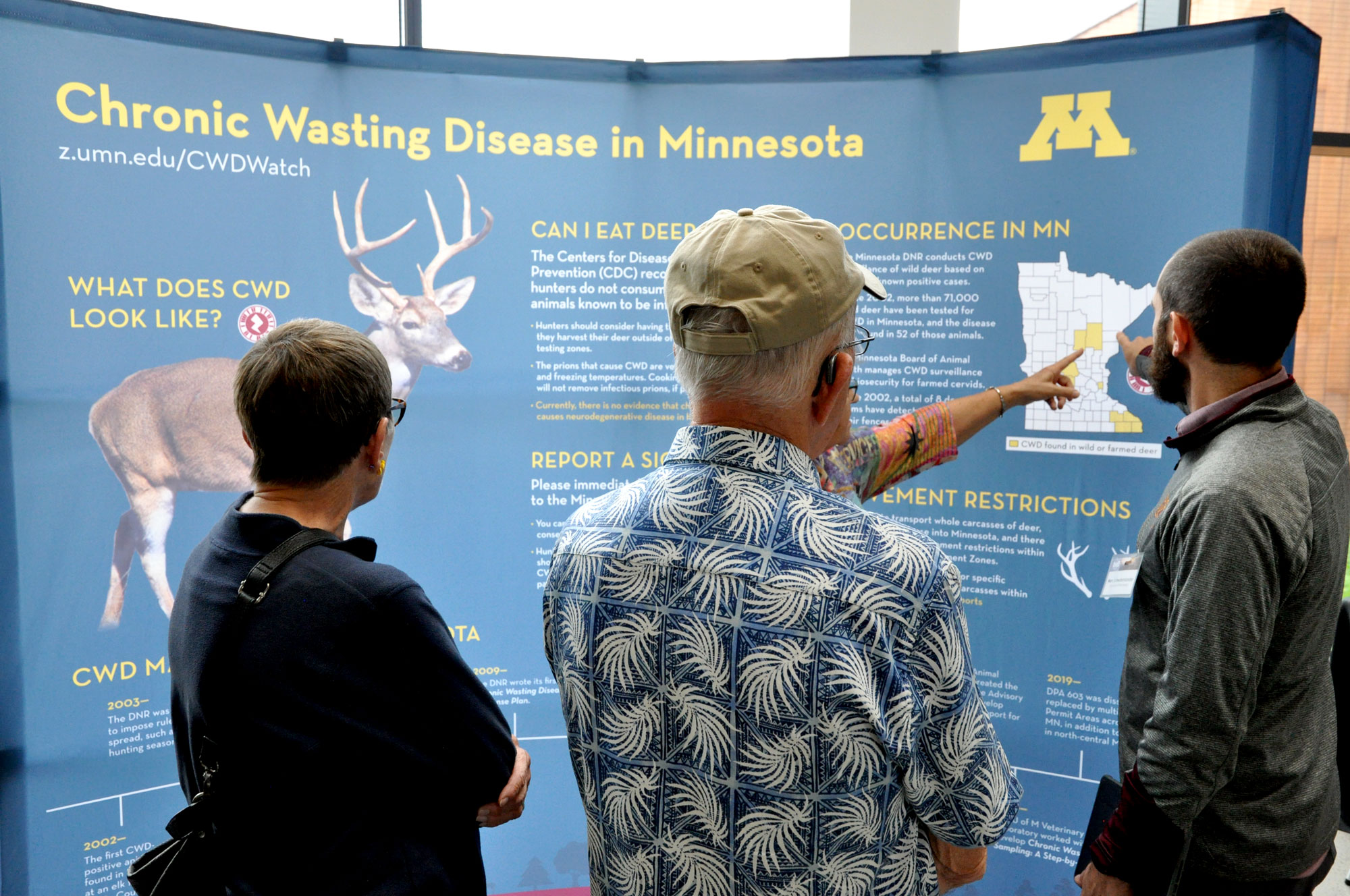

Visitors to the CAHFS and Bell Museum event on chronic wasting disease learned about the disease's impact in Minnesota. | Photo by Martin Moen

Minnesota’s rolling prairies and northern woodlands are home to an estimated 1 million wild deer. The animals are both a staple of the state’s heritage and a huge economic asset—deer are the most-hunted species in Minnesota and the sport contributes more than $1.3 billion to the state’s economy every year.

Chronic wasting disease (CWD), a fatal neurological disease that affects cervids, such as deer, moose, and elk, was first detected in domesticated deer in Minnesota in 2002 and in the state’s wild deer population in 2010. The contagion, which is related to mad cow disease, has spread to at least 26 states and the Alliance for Public Wildlife estimates the number of infected animals could increase by 20 percent every year. Experts worry that if the disease continues to gain new ground, it could eventually affect humans.

The Center for Animal Health and Food Safety (CAHFS) at the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) is working with Peter Larsen, PhD, an assistant professor of molecular biology in the CVM, and his team of engineers on the urgent need to educate Minnesotans about CWD. Last month, CAHFS launched their fall 2019 emerging issues webpage, CWD Watch, which is complete with videos, maps, and other scientific and animal health-based resources to help the public understand what is known and not yet known about CWD and its impact.

The team is also developing new technology that will prevent the elusive disease from spreading. “There are several teams from around the world coming together to develop new tools to address CWD, but the U of M brings this amazing multidisciplinary resource of faculty members and outside partners,” Larsen says. “When you bring all of us together, we can develop a diagnostic device that only the U of M has the infrastructure to produce.”

Early detection

Before he joined the U of M last year, Larsen researched genome sequencing and Alzheimer's disease at Duke University, for which he created a portable DNA sequencing lab. Larsen believes a similar mobile testing lab for CWD is not far out of reach—his team is aiming to have a functional prototype up and running within the next two years. After that, the device will undergo rigorous testing before a field-ready model can be deployed.

The lab would use similar biomarker technology used in Alzheimer's research in humans and fix the limitations that cause current CWD testing to fall short, all while using a device that fits in the palm of your hand.

“Current diagnostics are complex and require highly specialized staff,” explains Larsen. Currently, standard practice is to test brainstems or lymph nodes, meaning only euthanized animals are testing candidates, and current tests can’t screen environmental carriers such as soil, where the disease can live for up to a decade. Once animals are infected with the highly contagious disease, they can lurk for up to two years without showing signs, so testing the urine, blood, saliva, and droppings of live deer, elk, and moose is key to preventing hunters and farmers from unknowingly transporting infected animals.

“We believe that we can create a test that will identify CWD in preclinical stages, which means we would be able to identify the disease in live deer or in the environment," says Larsen. "The test would also provide a rapid positive or negative result for hunter-harvested animals.”

Using current technology, hunters have to wait several days to get test results, which still may produce false negatives for animals infected with an early stage of the disease. “Hunters can unknowingly transport animals infected with CWD because the animal will look perfectly healthy. There is no way to know if it has the disease,” says Larsen, whose rapid test could ultimately decrease the spread of CWD during the autumn hunting season, in which roughly 50,000 deer will be harvested in Minnesota alone.

Spreading the word, not disease

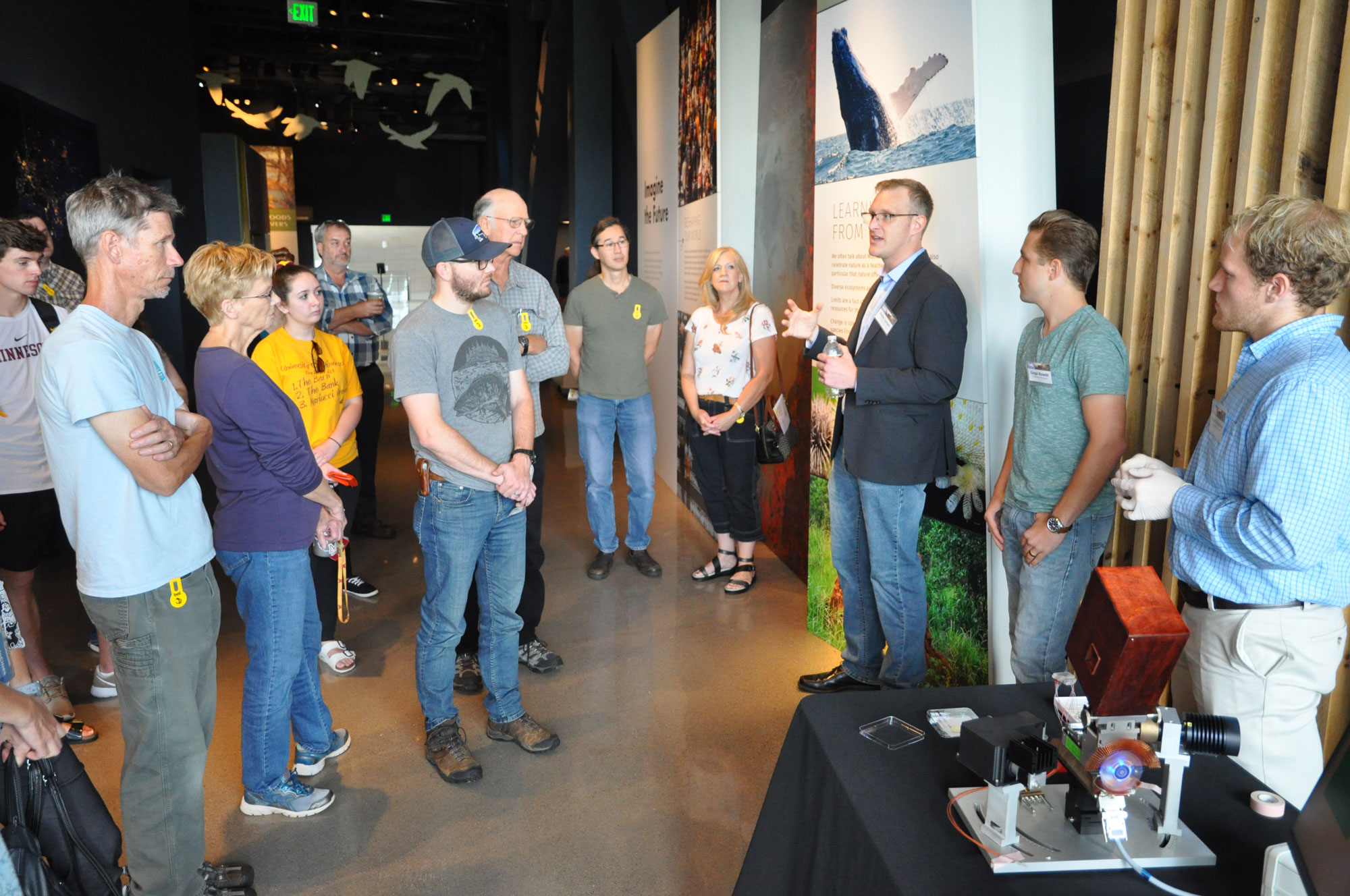

The U of M's Bell Museum, the state's official natural history museum and planetarium, joined forces with CAHFS in September to host Spotlight Science: Chronic Wasting Disease, which featured Larsen and three additional expert speakers, including two from the U of M: Roxanne Larsen, PhD, an anatomist and science communicator from the CVM, and Devender Kumar, BVSc & AH, MVSc, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate in the CVM. The third was Lou Cornicelli, a wildlife research manager at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, who has worked with CWD surveillance for 20 years and provided insight into the status of the disease and what the state is doing to prevent it.

“What I’ve noticed over the past couple of years is that there are a lot of questions and misunderstandings about the disease,” says Larsen, who feels education must work in tandem with technology for it to be effective.

The event featured interactive learning activities for children and adults and the opportunity for attendees to see CWD samples under a microscope. The newly remodeled Bell Museum was a scenic backdrop for the Saturday event. As guests also explored the Bell’s intricate dioramas showcasing scenes of Minnesota wildlife, they could situate discussions of CWD within the broader context of natural history and conservation.

Online resources including disease tracking and education are available through CAHFS Emerging Issues: CWD Watch.

See all - One to One Newsletter: October 2019